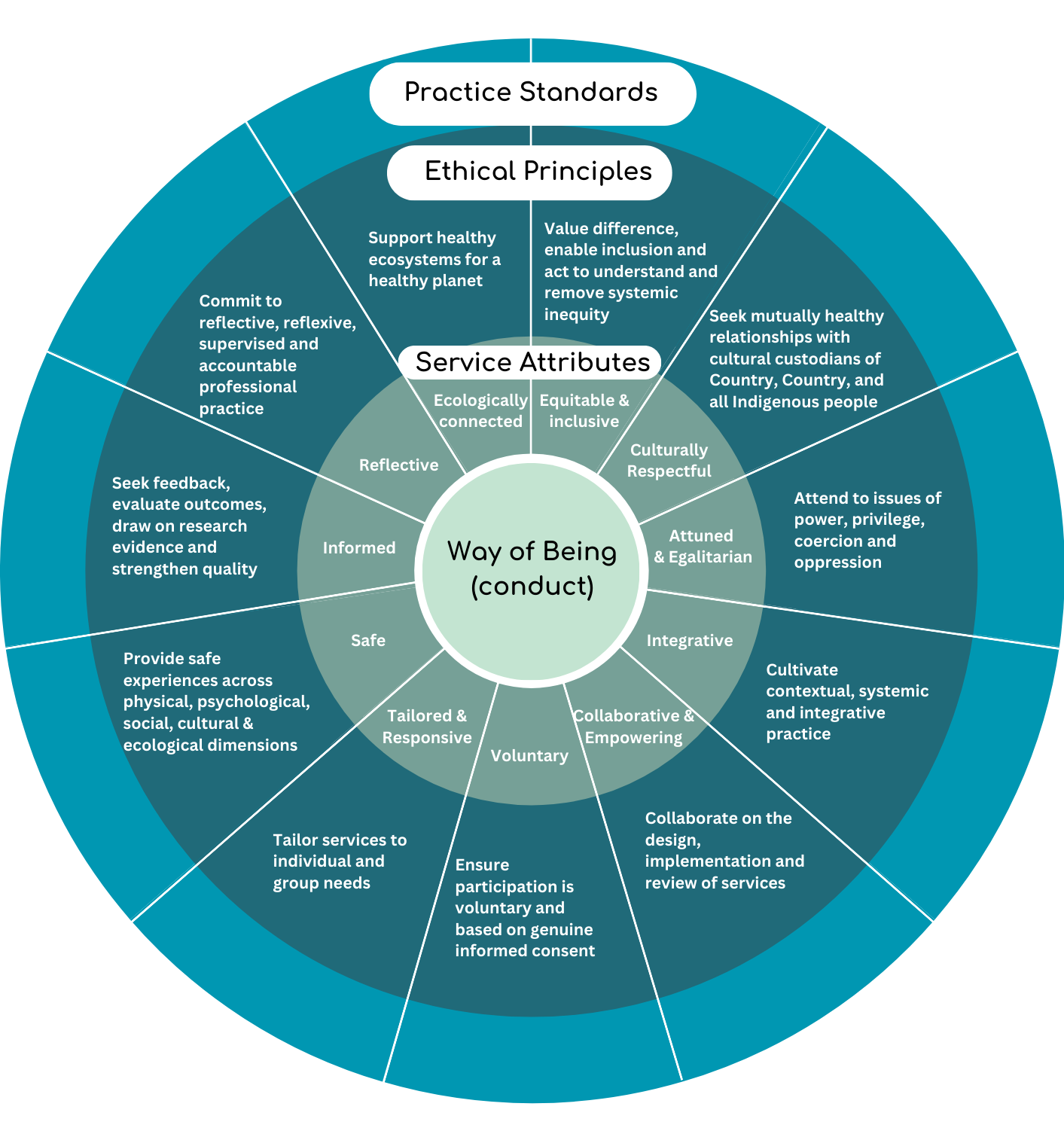

Outdoor Health Australia has drafted a quality framework to support outdoor health organisations, practitioners and participants. This draft framework is presented to the outdoor health sector for feedback and input. To contribute, please email [email protected].

Draft Framework Overview

Practice Standards

These practice standards are provided to guide organisations and individual practitioners in aligning with ethical

principles.

Ethical Principles

1. Show positive regard for all, value difference, enable inclusion, and act to understand and address systemic inequity

Definition

Valuing differences and being inclusive in outdoor health practices can help address structural disadvantages and create better experiences for all participants. Acting to better understand elements of systemic inequality and how they may be present in our own practice enables outdoor health services to contribute meaningfully to the health and wellbeing of our communities.

Service attributes

Equitable & Inclusive

Standards

Practitioners and service organisations:

- Offer engaging, safe and effective services for people from all walks of life.

- Identify and where possible, remove or reduce systemic and structural barriers to participation.

- Attend to personal biases and cultural blind spots to increase equity and justice with all participants and stakeholders.

- Seek to understand and remove forms of oppression, colonisation and structural disadvantage.

Examples of ethical practice

Following principles of universal design for physical environments and universal design for learning when developing or delivering experiences supports equal access. By identifying and addressing potential barriers to accessing services, and levels of comfort participants may have in using services, we will increase the appeal of our service for diverse clients. By offering different ways for participants to engage with experiences, and different ways of experiencing service satisfaction, all participants will experience feelings of success. Reflecting on personal cultural biases, and addressing personal and staff team blind spots in working with different client groups, is an ongoing work.

Contributing theories and evidence

- Social justice approaches

- Trauma theory

- Common elements approach

This principle is supported by several different yet connected bodies of science. Ecological theory, applied at many scales empirically demonstrates the relationship between diversity, the health of the system and the individuals within it (Jake M. Robinson et al., 2018). Access to nature and the associated benefits remains highly inequitable. As such OH practices need to engender an understanding of this inequity and act to address this within service provision (Jennings et al., 2016; Rigolon et al., 2021). OHA recommends that OH services integrate an understanding of intersectionality theory, among others, in support of efforts to navigate the ethics of inclusion and equity (Joy, 2019).

A recent scoping review* found discussion related to this ethical principle within the following literature.

Hall, C. M. (2019). Tourism and rewilding: An introduction–definition, issues and review. Journal of Ecotourism, 18(4), 297–308. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2019.1689988

Harper, N. J., & Fernee, C. R. (2022). Unpacking Relational Dignity: In Pursuit of an Ethic of Care for Outdoor Therapies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 766283. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.766283

Hooley, I. (2016). Ethical Considerations for Psychotherapy in Natural Settings. Ecopsychology, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2016.0008

Jeffery, H., & Wilson, L. (2017). New Zealand occupational therapists’ use of adventure therapy in mental health practice. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(1), 32–38.

King, B. C., Taylor, C. D., Garcia, J. A., Cantrell, K. A., & Park, C. N. (2022). Ethics and ecotherapy: The shared experiences of ethical issues in practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 0(0), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2022.2029512

Moriggi, A., Soini, K., Bock, B. B., & Roep, D. (2020). Caring in, for, and with nature: An integrative framework to understand green care practices. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(8). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12083361

Pearce, L. M. (2018). Affective ecological restoration, bodies of emotional practice. International Review of Environmental History, 4(1), 167–189.

Reese, R. F. (2018). EcoWellness: Contextualizing Nature Connection in Traditional Clinical and Educational Settings to Foster Positive Childhood Outcomes. Ecopsychology, 10(4), 289–300. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0031

Stålhammar, S., & Thorén, H. (2019). Three perspectives on relational values of nature. Sustainability Science, 14(5), 1201–1212. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00718-4

Stea, T. H., Jong, M. C., Fegran, L., Sejersted, E., Jong, M., Wahlgren, S. L. H., & Fernee, C. R. (2022). Mapping the Concept, Content, and Outcome of Family-Based Outdoor Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Mental Health Problems: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105825

Taranrød, L. B., Pedersen, I., Kirkevold, Ø., & Eriksen, S. (2021). Being sheltered from a demanding everyday life: Experiences of the next of kin to people with dementia attending farm-based daycare. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 16(1), 1959497. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2021.1959497

2. Seek mutually healthy relationships with cultural custodians of Country, Country, and with all Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Indigenous peoples

Definition

In the Australian continent, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have cared for Country, family and community for millennia. Outdoor practices take place on unceded Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander land and sea Country. Acknowledging and respecting the cultural custodianship of Country by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples wherever possible is a way of respecting longstanding care and wisdom.

Service attributes

Respectful of Indigenous cultures, places and peoples

Standards

Practitioners and service organisations:

- Build healthy relationships with Indigenous/First nations peoples.

- Involve cultural knowledge holders as partners or mentors where possible.

- Design and plan for active caring for country activities as part of services.

- Use local names for Country where known.

Examples of ethical practice

Where possible, we identify and seek permission from cultural custodians of the land or sea Country we wish to access for services. Gaining information about cultural history of the place, and appropriate knowledge of current cultural practices will enrich our services. By getting to know local cultural custodians we are showing respect, and increasing cultural safety for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal participants alike.

Contributing theories and evidence

- Aboriginal/ Indigenous healing practices

- Decolonisation

- Care for Country

C. Atkinson, (2020) & J. Atkinson & Stawiarski, (2021) describe the many deep synergies between Indigenous ways of doing and being and contemporary OH practices. In Australia, as with other settler colonial societies, care is required to avoid perpetuating colonising acts, particularly by non-indigenous peoples. Tujague & Ryan (2021) emphasise the need for genuine, mutually respectful relationships and embedded understanding of the traumatic impacts of colonisation. Prehn (2024) promotes a strength based approach in partnering with indigenous peoples and communities.

A recent scoping review* found discussion related to this ethical principle within the following literature.

Atkinson, C., & Gregory, S. (2020). Trauma Informed Approaches [Plenary Session]. Nature & Health Online Symposium, Australia. https://outdoorhealthcare.org.au/naidoc-2020/

Atkinson, J., & Stawiarski, B. (2021). Indigenous Approaches in Outdoor Healthcare: A Yarn [Plenary Session]. Outdoor Health Symposium, Online.

Drost, J. L. (2019). Developing the Alliances to Expand Traditional Indigenous Healing Practices Within Alberta Health Services. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 25(S1), S69–S77. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2018.0387

King, B. C., Taylor, C. D., Garcia, J. A., Cantrell, K. A., & Park, C. N. (2022). Ethics and ecotherapy: The shared experiences of ethical issues in practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 0(0), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2022.2029512

Ljubicic, G. J., Mearns, R., Okpakok, S., & Robertson, S. (2021). Learning from the land (Nunami iliharniq): Reflecting on relational accountability in land-based learning and cross-cultural research in Uqšuqtuuq (Gjoa Haven, Nunavut). Arctic Science, 8(1), 252–291. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2020-0059

Lokugamage, A. U., Ahillan, T., & Pathberiya, S. D. C. (2020). Decolonising ideas of healing in medical education. Journal of Medical Ethics, 46(4), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2019-105866

Prehn, J., & Guerzoni, M. A. (2024). Using Indigenous Standpoint Theory with the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529682922

Tujague, N. A., & Ryan, K. L. (2021). Ticking the box of “cultural safety” is not enough: Why trauma-informed practice is critical to Indigenous healing. Rural and Remote Health, 21(3), 1–5.

3. Attend to issues of power and privilege, coercion and oppression

Definition

Increasing our personal awareness of our own privileges, powers and advantages/ disadvantages enables us to better attend to these dimensions in our practice with others, and support anti-oppressive and decolonising practices. Manipulating, forcing or coercing participants into situations, actions or experiences can be oppressive, colonising, and potentially harmful. Understanding that there are both personal and structural dimensions to issues of consent and voluntary participation enables practice to proceed safely and equitably.

Service attributes

Attuned & Egalitarian

Standards

Practitioners and service organisations:

- Are personally aware of the inherent power within their various roles, responsibilities and positions as service providers.

- Are aware of and attend to the privileges we each carry and attend to the potential harms that can result.

- Identify and reduce forms of oppression, coercion and authoritarian decision-making that may lead to harm to participants, practitioners and stakeholders.

- Prevent all kinds of abuse to participants, including physical-, sexual-, emotional- and socio-cultural harms.

- Comply with and refer people to relevant local, state or national frameworks such as: MARAM framework (family violence); Vic Child Safe Standards (child safety), National Child Safe Principles; etc.

Examples of ethical practice

Identifying specific personal and professional experiences of power, privilege, powerlessness and disadvantage, will help us to locate our personal and professional selves within our wider social-cultural-political contexts. Where possible, we attempt to reduce the power we have as adult-practitioner-facilitators by offering options and choices to participants, and when appropriate, handing control and decision-making power to them. By attending to our own power and privilege as adult-practitioner-facilitators, we can more readily remove, or at least reduce and be more aware of the power or coercion we might otherwise accidentally wield over participants.

Contributing theories and evidence

- Intersectionality

- Feminist theory

- Polyvagal theory

Navigating the terrain of power relations and understanding privilege at individual and collective levels is a significant and ongoing task for ethical OH services. Knowles et al. (2024) draws on literature intersecting the OH sector to invite an ethic of meaningful accountability to understanding privilege enacted in OH service delivery. While understanding power relations has been low hanging fruit for therapeutic practices generally, issues across domains of privilege impact on both the design and implementation of OH practices and their accessibility to marginalised groups (Benz et al., 2022; Gray et al., 2022; King et al., 2022; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Mitten, 2018, 2020; Plesa, 2019; Tujague & Ryan, 2021).

A recent scoping review* found discussion related to this ethical principle within the following literature.

King, B. C., & McIntyre, C. J. (2018). An Examination of the Shared Beliefs of Ecotherapists. Ecopsychology, 10(2), 117–126. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0014

King, B. C., Taylor, C. D., Garcia, J. A., Cantrell, K. A., & Park, C. N. (2022). Ethics and ecotherapy: The shared experiences of ethical issues in practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 0(0), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2022.2029512

Moriggi, A., Soini, K., Bock, B. B., & Roep, D. (2020). Caring in, for, and with nature: An integrative framework to understand green care practices. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(8). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12083361

Pearce, L. M. (2018). Affective ecological restoration, bodies of emotional practice. International Review of Environmental History, 4(1), 167–189.

Stålhammar, S., & Thorén, H. (2019). Three perspectives on relational values of nature. Sustainability Science, 14(5), 1201–1212. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00718-4

4. Cultivate contextual, systemic and integrative practices

Definition

All human relationships occur in the context of place, community, culture and time, from micro through to meta levels of relationship and interaction. Each of these levels of influence contribute to the socio-ecological system surrounding individual humans, including outdoor health practitioners, participants, families, communities, and wider stakeholders.

Service attribute

Integrative

Standards

Practitioners and service organisations:

- Identify the systemic and structural socio-cultural context of the service and its intended aims.

- Take into account systemic and structural impacts on health as part of service design and delivery.

- Consider transdisciplinary strengths and opportunities.

Examples of ethical practice

Seeking to understand the longer and wider trajectories of participants, and their intersecting systems in order to tailor services to their longer and broader needs. Strive to design experiences that enable a supportive pathway into, through, and beyond offered services. Taking responsibility for the often ‘brief’ nature of offered services, and sharing responsibility with the participant for their longer life pathway.

Contributing theories and evidence

- Social determinants of health

- Cybernetics

- Systems theory

A recent scoping review* found discussion related to this ethical principle within the following literature.

Benz, A., Formuli, A., Jeong, G., Mu, N., & Rizvanovic, N. (2022). Environmental psychology: Challenges and opportunities for a sustainable future. PsyCh Journal, 11(5), 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.585

Drost, J. L. (2019). Developing the Alliances to Expand Traditional Indigenous Healing Practices Within Alberta Health Services. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 25(S1), S69–S77. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2018.0387

King, B. C., & McIntyre, C. J. (2018). An Examination of the Shared Beliefs of Ecotherapists. Ecopsychology, 10(2), 117–126. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0014

King, B. C., Taylor, C. D., Garcia, J. A., Cantrell, K. A., & Park, C. N. (2022). Ethics and ecotherapy: The shared experiences of ethical issues in practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 0(0), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2022.2029512

Kolb, A., & Kolb, D. (2018). Eight important things to know about the experiential learning cycle. Australian Educational Leader, 40(3), 8–14.

Ljubicic, G. J., Mearns, R., Okpakok, S., & Robertson, S. (2021). Learning from the land (Nunami iliharniq): Reflecting on relational accountability in land-based learning and cross-cultural research in Uqšuqtuuq (Gjoa Haven, Nunavut). Arctic Science, 8(1), 252–291. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2020-0059

Moriggi, A., Soini, K., Bock, B. B., & Roep, D. (2020). Caring in, for, and with nature: An integrative framework to understand green care practices. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(8). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12083361

Pearce, L. M. (2018). Affective ecological restoration, bodies of emotional practice. International Review of Environmental History, 4(1), 167–189.

Stålhammar, S., & Thorén, H. (2019). Three perspectives on relational values of nature. Sustainability Science, 14(5), 1201–1212. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00718-4

5. Collaborate on the design, implementation and review of services

Definition

Respecting that participants know most about their own experiences and placing them at the centre of our work is empowering and leads to empowered outcomes. Outdoor health practices are most effective when the participant is co-pilot and has agency in decision-making.

Service attributes

Collaborative & Empowering

Standards

Practitioners and service organisations:

- Provide timely information and appropriate engagement options for participants based on service intention and target group.

- Where possible, offer participants opportunities to co-create their experience.

Examples of ethical practice

Where possible, we design services with service users, including participants, parents/carers and significant others. By collaborating with service users of different perspectives, we will better be able to match service to need, and support the efficacy of the service for service users. Involving service users in reflective co-design, service implementation, regular feedback, and action research processes will support refinement and enhancement of the service, helping it to become more safe and more effective.

Contributing theories and evidence

- Co-design

- Stages of Change

- Depth of intervention

While the term co-design has recently gained prominence, the concept of co-creating or co-constructing therapeutic experiences has existed within the OH literature for decades (Hovelynck, 2002). Knowles et al. (2024) described the skill of co-designing as an essential area of competence for ethical practice. This ethic is well supported in contemporary OH practice (Harper & Fernee, 2022; Hooley, 2016; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Moriggi et al., 2020)

A recent scoping review* found discussion related to this ethical principle within the following literature.

Harper, N. J., & Fernee, C. R. (2022). Unpacking Relational Dignity: In Pursuit of an Ethic of Care for Outdoor Therapies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 766283. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.766283

Hooley, I. (2016). Ethical Considerations for Psychotherapy in Natural Settings. Ecopsychology, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2016.0008

Lokugamage, A. U., Ahillan, T., & Pathberiya, S. D. C. (2020). Decolonising ideas of healing in medical education. Journal of Medical Ethics, 46(4), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2019-105866Moriggi, A., Soini, K., Bock, B. B., & Roep, D. (2020). Caring in, for, and with nature: An integrative framework to understand green care practices. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(8). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12083361

6. Ensure participation is voluntary and based on genuine informed consent

Definition

Ensuring that participants are given authentic choice if and how they participate in the service at the outset is vital. Deliberate consideration is given to the provision of soft entry and exit points throughout the service model. Genuine consent requires the provision of genuine, clear, understandable and understood information at the outset, and throughout, to ensure that participation is both informed and voluntary. Consent of caregivers does not assure consent of participants.

Service attributes

Voluntary

Standards

Practitioners and service organisations:

- Provide participants with accurate, accessible information about the service and each aspect of participation. The level of information provided should be sufficient for each participant to make informed choices about whether and how they participate.

- Provide open opportunities for participants to have genuine choice, to step in, or step out of service delivery at any time, or if not at any time, at key stated timepoints.

Examples of ethical practice

Where possible, we provide information about the service to service users in a variety of ways, that may include flyers, information sessions, interviews, phone calls, and ‘taster’ experiences. Knowing not just ‘when and what’, but also ‘who and how’, are important pieces of information for service users to know and understand before opting to step in and participate. By providing a staged progression of experiences, with each stage having its own entry point for further commitment and exit point for authentic and dignified exit, participants will have an increased sense of choice and control throughout.

Contributing theories and evidence

- Informed consent

- Voluntary participation

- Duty of care

A recent scoping review* found discussion related to this ethical principle within the following literature.

Bradford, D. L. (2019). Ethical Issues in Experiential Learning. Journal of Management Education, 43(1), 89–98. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562918807500

Haber, R., & Deaton, J. D. (2019). Facilitating an Experiential Group in an Educational Environment: Managing Dual Relationships. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 69(4), 434–458. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207284.2019.1656078

Harper, N. J., & Fernee, C. R. (2022). Unpacking Relational Dignity: In Pursuit of an Ethic of Care for Outdoor Therapies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 766283. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.766283

Hooley, I. (2016). Ethical Considerations for Psychotherapy in Natural Settings. Ecopsychology, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2016.0008

King, B. C., Taylor, C. D., Garcia, J. A., Cantrell, K. A., & Park, C. N. (2022). Ethics and ecotherapy: The shared experiences of ethical issues in practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 0(0), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2022.2029512

Reese, R. F. (2018). EcoWellness: Contextualizing Nature Connection in Traditional Clinical and Educational Settings to Foster Positive Childhood Outcomes. Ecopsychology, 10(4), 289–300. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0031

Stea, T. H., Jong, M. C., Fegran, L., Sejersted, E., Jong, M., Wahlgren, S. L. H., & Fernee, C. R. (2022). Mapping the Concept, Content, and Outcome of Family-Based Outdoor Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Mental Health Problems: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105825

7. Tailor services to individual and group needs and strengths

Definition

Peoples’ needs vary based on their specific bio-, psycho-, social-, cultural- and ecological factors. Individuals’ needs, hopes and intentions are subjective and time-specific; their safety, regulation, learning, reflection, healing and growth is specific to their context, relationships and readiness. Ethical, effective group-based practice includes having the information and capacity to tailor experiences for participating individuals, within the group space, and being ready to adapt to changing individual and group needs over time.

Service attribute

Tailored & Responsive

Standards

Practitioners and service organisations:

- Have a comprehensive understanding of their participant cohorts.

- Have systems to ensure the needs, intentions and contexts of individuals and particular groups (1) are understood and (2) inform the design, planning and delivery of a service.

Examples of ethical practice

Where possible, we gain a comprehensive understanding of the needs, hopes and strengths of participating individuals, to the degree they are willing to share that information, over time. With good knowledge about participating individuals, we are readied to provide a safe and appropriate group space that is conducive and supportive of individuals needs and wishes. Moving into group-based experiences without prior knowledge of individuals, and without the informed consent of individuals to participate in that group raises risks of socio-cultural harms occurring within the group to participating group members. Safe groups can take on a life of their own, and help enhance outcomes for all participating individuals.

Contributing theories and evidence

- Group therapy

- Individual and group goals

- Brief therapy

Responding to participant hopes, needs and interests and tailoring services to meet these is essential for effective OH practice (Harper & Fernee, 2022; Hooley, 2016; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Moriggi et al., 2020). Further, if participant needs are not taken into account and addressed within the service design, there is likelihood they could do further harm (Masterton et al., 2022). Not only do OH services need to be matched and tailored to participant needs they need to be tailored matched to the context and teachers skills, knowledge and capacity (Chawla et al., 2014).

A recent scoping review* found discussion related to this ethical principle within the following literature.

Harper, N. J., & Fernee, C. R. (2022). Unpacking Relational Dignity: In Pursuit of an Ethic of Care for Outdoor Therapies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 766283. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.766283

Hooley, I. (2016). Ethical Considerations for Psychotherapy in Natural Settings. Ecopsychology, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2016.0008

Lokugamage, A. U., Ahillan, T., & Pathberiya, S. D. C. (2020). Decolonising ideas of healing in medical education. Journal of Medical Ethics, 46(4), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2019-105866

Moriggi, A., Soini, K., Bock, B. B., & Roep, D. (2020). Caring in, for, and with nature: An integrative framework to understand green care practices. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(8). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12083361

8. Provide experiences that are safe across physical, psychological, social, cultural, and ecological dimensions

Definition

It is important that our risk assessment and mitigation strategies include consideration of risks across multiple dimensions, and that our practices seek to balance ‘risk of harm’ with ‘potential for benefits’ throughout our planning, implementation and review processes, for participants, practitioners and all stakeholders.

Service attribute

Safe

Standards

Practitioners and service organisations:

- Understand that working with people involves multi-dimensional risks that need to be managed.

- Develop and maintain systems that enable safe-enough, effective practice and avoid physical, psychological, socio-cultural, spiritual and ecological harms for participants and staff.

- Comply with child safe and work health and safety legislation and any standards relevant to your practice or registration (e.g. Australian Adventure Activity Standards, PACFA Standards).

Examples of ethical practice

Holistic assessment of participating individual’s needs and strengths, careful formation of a ‘safe enough’ social space, and comprehensive co-design will help to both increase safety and decrease risks across physical-, mental-, emotional-, social-, cultural-, spiritual- and ecological dimensions for participating individuals and practitioners. Given the multidimensional milieu we offer within outdoor health services, development of a holistic safetynet is a central responsibility for practitioners and services.

Contributing theories and evidence

- Bio-psycho-sociocultural-ecological wellbeing (BPSCE)

- Circle of Security

- Neurosequential model

A recent scoping review* found discussion related to this ethical principle within the following literature.

Bradford, D. L. (2019). Ethical Issues in Experiential Learning. Journal of Management Education, 43(1), 89–98. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562918807500

Hall, C. M. (2019). Tourism and rewilding: An introduction–definition, issues and review. Journal of Ecotourism, 18(4), 297–308. Scopus.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2019.1689988

Harper, N. J., & Fernee, C. R. (2022). Unpacking Relational Dignity: In Pursuit of an Ethic of Care for Outdoor Therapies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 766283. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.766283

King, B. C., Taylor, C. D., Garcia, J. A., Cantrell, K. A., & Park, C. N. (2022). Ethics and ecotherapy: The shared experiences of ethical issues in practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 0(0), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2022.2029512

Reese, R. F. (2018). EcoWellness: Contextualizing Nature Connection in Traditional Clinical and Educational Settings to Foster Positive Childhood Outcomes. Ecopsychology, 10(4), 289–300. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0031

9. Commit to reflective, reflexive, supervised, and accountable professional practice

Definition

Given the complex decision-making involved in providing safe and effective outdoor health practices, it is critical that practitioners commit to increasing their self awareness and skills in reflexive practice through ongoing commitment to reflection, supervision and professional development, within a supportive and critical ‘Community of practice’. While outdoor health practitioners combine multiple dimensions in their practice, it is their regulated wise ‘self’ that is the primary therapeutic instrument, decision-maker and power-broker within outdoor health experiences.

Service attribute

Reflective

Standards

Practitioners and service organisations:

- Recognise and act within scope of professional competence.

- Commit to regular ongoing supported professional supervision.

- Commit to regular ongoing supported professional professional development.

- Embed research evidence, borrowed knowledge and practice wisdom within service design, delivery and review.

- Maintain rigorous accountability to participants and all stakeholders in relation to stated and delivered professional practice.

- Recognise that professional pathways involve trajectories from less experience, to development and specialisation, with changing professional scope.

- Attend to and address conflict of interest or values between practitioner and participant and other stakeholders.

Examples of ethical practice

Practitioners who undertake regular critical self reflection, supported by trained and experienced supervisors, and surrounded by a caring and honest community of peers, will be best prepared to make ethical safe and effective practice-related decisions and actions. It is when we are taken by surprise, feeling triggered, frustrated, tired, cynical, undervalued or overloaded that our capacity for good safe practice will be diminished. Personal nourishment through regular participation in active enjoyable experiences out-of-doors with friends and family also supports good practice!

Contributing theories and evidence

- Professional scope

- Trauma-informed practice

- Evidence-informed practice

A recent scoping review* found discussion related to this ethical principle within the following literature.

Bradford, D. L. (2019). Ethical Issues in Experiential Learning. Journal of Management Education, 43(1), 89–98. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562918807500

King, B. C., Taylor, C. D., Garcia, J. A., Cantrell, K. A., & Park, C. N. (2022). Ethics and ecotherapy: The shared experiences of ethical issues in practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 0(0), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2022.2029512

Moriggi, A., Soini, K., Bock, B. B., & Roep, D. (2020). Caring in, for, and with nature: An integrative framework to understand green care practices. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(8). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12083361Reese, R. F. (2018). EcoWellness: Contextualizing Nature Connection in Traditional Clinical and Educational Settings to Foster Positive Childhood Outcomes. Ecopsychology, 10(4), 289–300. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0031

10. Seek feedback, evaluate outcomes, draw on research evidence and strengthen quality

Definition

To monitor and manage the benefits and risks of outdoor health practices for participants, practitioners and natural environments, it is important to draw on research evidence, monitor, evaluate and refine practices over time. Participant and stakeholder feedback should be central to this process.

Service attribute

Informed

Standards

Practitioners and service organisations:

- Establish appropriate monitoring and evaluation strategies to assess safety, quality and fidelity of the service.

- Ensure participant and stakeholder feedback is built into program design and evaluation strategies.

- Strengthen service models and practice approaches through rigorous review and refinement processes.

Examples of ethical practice

Practitioners and services that seek feedback from participants, parents/carers, and wider stakeholders will be best informed about ways to refine and enhance their service delivery. With the exponential increase in research and evidence relating to nature connection, physical activity, group-based experiences and psychological care, there is no shortage of guidance for practitioners and services. By drawing on local cultural knowledge, practice wisdom, researched evidence, lived experience, and participant feedback, service quality and safety will be strengthened, and participant satisfaction increased.

Contributing theories and evidence

- Quality assurance

- Evaluation

- Feedback informed treatment

A recent scoping review* found discussion related to this ethical principle within the following literature.

Harper, N. J., & Fernee, C. R. (2022). Unpacking Relational Dignity: In Pursuit of an Ethic of Care for Outdoor Therapies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 766283. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.766283

Hooley, I. (2016). Ethical Considerations for Psychotherapy in Natural Settings. Ecopsychology, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2016.0008

Moriggi, A., Soini, K., Bock, B. B., & Roep, D. (2020). Caring in, for, and with nature: An integrative framework to understand green care practices. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(8). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12083361

11. Support healthy ecosystems for a healthy planet

Definition

Sustainable practices are based on ecological interdependence, recognising that ecological and environmental costs and benefits are also human and economic costs and benefits. Ethically sustainable practices reduce ecological-, environmental-, human- and economic costs and harms, including hidden long-term harms, and maximise restorative benefits.

Service attribute

Ecologically connected

Standards

Practitioners and service organisations:

- Embed and model practices that value consideration of the health of natural environments and the planet.

- Consider the health and sustainability of participants, practitioners, organisations and other stakeholders throughout service design and delivery.

- Assess and implement changes to practices and service models to maximise health and sustainability of individuals and the natural environment.

Examples of ethical practice

Outdoor health services that meaningfully and carefully integrate nature as co-facilitator, and offer opportunities to care for nature and natural environments within the program design will be concurrently promoting human and environmental health. An outdoor health service that does not demonstrate care for nature, or worse, contributes to the damage and destruction of natural environments, is not a healthy outdoor health service. Giving participants opportunities to ‘Care for Country’ and ‘give back to nature’ will support the health of humans and all beings. As climate change and the impacts of biodiversity loss are increasingly felt around the world over time, environmental activism will become a necessary antidote for symptoms of eco anxiety, stress, despair and trauma, and a critical element of outdoor health services.

Contributing theories and evidence

- Biophilia hypothesis

- Social ecology

- Deep ecology

A recent scoping review* found discussion related to this ethical principle within the following literature.

Benz, A., Formuli, A., Jeong, G., Mu, N., & Rizvanovic, N. (2022). Environmental psychology: Challenges and opportunities for a sustainable future. PsyCh Journal, 11(5), 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.585

Galardi, M., De Santis, M., Moruzzo, R., Mutinelli, F., & Contalbrigo, L. (2021). Animal assisted interventions in the green care framework: A literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189431

Hall, C. M. (2019). Tourism and rewilding: An introduction–definition, issues and review. Journal of Ecotourism, 18(4), 297–308. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2019.1689988

Harper, N. J., & Fernee, C. R. (2022). Unpacking Relational Dignity: In Pursuit of an Ethic of Care for Outdoor Therapies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 766283. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.766283

King, B. C., Taylor, C. D., Garcia, J. A., Cantrell, K. A., & Park, C. N. (2022). Ethics and ecotherapy: The shared experiences of ethical issues in practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 0(0), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2022.2029512

Lokugamage, A. U., Ahillan, T., & Pathberiya, S. D. C. (2020). Decolonising ideas of healing in medical education. Journal of Medical Ethics, 46(4), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2019-105866

Pearce, L. M. (2018). Affective ecological restoration, bodies of emotional practice. International Review of Environmental History, 4(1), 167–189.

Plesa, P. (2019). A theoretical foundation for ecopsychology: Looking at ecofeminist epistemology. New Ideas in Psychology, 52, 18–25. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.10.002

Reese, R. F. (2018). EcoWellness: Contextualizing Nature Connection in Traditional Clinical and Educational Settings to Foster Positive Childhood Outcomes. Ecopsychology, 10(4), 289–300. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0031

Endnote or Footnote* Knowles, B., Marsh, P., Prehn, J., & Maxwell, H. (2024). Addressing ethical issues in outdoor health practice: A scoping review. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-024-00160-w

About this framework

Outdoor Health Australia has drafted a quality framework to support outdoor health organisations, practitioners and participants. While we celebrate our diverse practices we also acknowledge our sector’s responsibility to those it aims to serve. To be effective, practices must be evidence-informed, safe and ethical (do no harm to participants).

A shared set of ethical principles and standards of practice can:

- Offer consistent pathways towards effective practice and avoiding harm, even across diverse practices

- Protect participants from harmful practices

- Increase validity and therefore support and funding for nature-based practices as public health and therapeutic options

- Help insurers to understand the consideration and management of some risks with which they may be unfamiliar.

Limitations of the framework

We recognise that these OHA Ethical principles are a ‘work in progress’, in need of further refinement, clarification and expansion over time. We look forward to future efforts that seek to clarify what outdoor health is not, including naming-up of harmful practices and non-evidenced practices. Further areas of consultation and focused effort include: Duty of care, Age of consent, Cultural safety, Gendered safety, and the application of neuroscience in outdoor health practice.

A next wave of work on these OHA Ethical principles will involve development of good practice guidance notes, an Accreditation framework, and a Complaints and Grievance process that is suitable for supporting the safety of participants, stakeholders and practitioners within our volunteer-led community and organisation.

This draft framework is presented to the outdoor health sector for feedback and input. To contribute, please email [email protected].

Development of the new draft ethical principles

In 2008, the Australian Association for Bush Adventure Therapy (AABAT), in consultation with the bush adventure therapy community developed a set of ethical principles which were endorsed by membership at the annual forum in Victoria, 2009 and reviewed again at the annual forum in the Northern Territory, 2015.

The new draft list of Ethical Principles is derived from a synthesis of the findings from the existing ethical principles (AABAT Inc, 2009), a literature review of ethical and effective practice for outdoor adventure interventions with young people who have experienced early life adversities and trauma (Pryor, Pryor & Carpenter 2018), a recent scoping review of Ethics in OH practice (Knowles, 2024), and comparable health and outdoor leadership ethical practice frameworks (AASW, 2020; ACSQHC, 2021; APS Ltd, 2018; Erin, 2016; OCA, 2019; PACFA, 2017). A team of three examined each principle in context of this research, the original AABAT principles and reflections on the social, sectoral, and governmental needs that OHA supports.

- AABAT Inc. (2009). Ethical Principles – Australian Association for Bush Adventure Therapy Inc. https://aabat.org.au/ethical-principles/

- AASW. (2020). AASW Code of Ethics 2020. Australian Association of Social Workers. https://www.aasw.asn.au/practitioner-resources/code-of-ethics

- ACSQHC. (2021). National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (second edition) | Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/national-safety-and-quality-health-service-standards-second-edition

- APS Ltd. (2018). APS Code of Ethics. The Australian Psychological Society Limited. https://psychology.org.au/getmedia/d873e0db-7490-46de-bb57-c31bb1553025/18aps-code-of-ethics.pdf

- Erin, M. (2016). Self Regulating Health Profession Peak Bodies Membership Standards. National Alliance of Self Regulating Health Professions. https://nasrhp.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/SR_Standards_Full_Dec_2.pdf

- Knowles, B., Marsh, P., Prehn, J., & Maxwell, H. (2024). Addressing ethical issues in outdoor health practice: A scoping review. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-024-00160-w

- OCA. (2019). Australian Adventure Activity Standard and associated Good Practice Guides—Outdoor Council of Australia [Sector Resource]. https://australianaas.org.au/

- Pryor, A. Pryor, R. & Carpenter, C. (2018). Outdoor Adventure Interventions – Young People and Adversity: A Literature Review. Berry Street Victoria Inc.

- PACFA. (2017). PACFA: Code of Ethics. Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia. https://www.pacfa.org.au/common/Uploaded%20files/PCFA/Documents/Documents%20and%20Forms/PACFA-Code-of-Ethics-2017.pdf

AABAT’s original Ethical Principles

BAT practitioners work towards:

- Positive regard for all people

- Respect for differences in culture, gender, age and identity

- Strong family and community connections

- Transparency, Informed consent, Confidentiality

- Voluntary participation (within the confines of service type)

- Selection for ‘readiness’ to participate

- Attention to individual and group needs and hopes

- Supportive physical, psychological and social environments

- Tailored adventure experiences

- Provision of options and choices (including supported exits)

- Respect for cultural custodianship of country

- Increasing self awareness and reflexive practice

- Safety and no harm to self, others or natural environments